Introduction

This protocol will describe the planned work for a systematic review as described by Booth and colleagues (2022). A systematic review seeks, methodically and in a transparent manner, to search for, appraise, and synthesise research evidence from all relevant studies on a specific topic (Granth & Booth, 2009). The topic for the planned systematic review is positive factors facilitating collaboration between early childhood education and care (ECEC) institutions, and multilingual parents. Initially, background, theory, and research-based knowledge relating to collaboration between ECEC institutions and parents are presented, and earlier relevant reviews are discussed. Thereafter the aims, research questions, and method for conducting the systematic review are presented.

In the planned review, the following terms will be used1: multilingual, minority language, and foreign background. Multilingual refers to a person who uses more than one language on an everyday basis (Wedin, 2017). The definition of minority language applied here is derived from the Swedish Institute for Language and Folklore (ISOF, 2021), and incorporates all languages spoken in a land, except for the majority or national language(s). Majority or national language, in this study, aligns with the definition of the Council of Europe as stated in the Languages of Schooling – Language Policy (Council of Europe, n. d.), and refers to the language used in schools and as a subject in schools.2 People with a foreign background are defined as persons either born in a foreign country or having two parents born in a foreign country (SCB, 2002)3. The term parents will be used as a concept, and includes single parents and others recognised by law as caregivers.

Background

Laws, curriculums, and other policy documents in the Scandinavian countries (Kunnskapsdepartementet, 2017; Skolverket, 2018), as well as in an international context (Anders et al., 2019; Epstein, 2018) emphasise parental involvement as being significant for child-centred practice. Parental influence and participation are also highlighted in different studies as being meaningful to children’s development, learning, and school success (Anders et al., 2019; Epstein, 2018; Hamilton et al., 2000; Tallberg-Broman, 2009). The ruling discourse, according to Markström and Simonsson (2017), is that collaboration and cooperation between ECEC institutions and parents is in ‘the best interest of the child’ (p. 179). However, Schmidt and Alasuutari’s (2023) discussion of policy ideals for parental cooperation in ECEC shows a change from ‘not only [having] the child [as] the policy target for societal goals and ideals, [but] so too the parent’ (p. 10). In Denmark, it is the ‘home-learning environment’ (p. 2) rather than partnership that is the dominant ideal on the government level. This is an example of a transformation from focusing on the child, pedagogical practice, and cooperation to addressing, and thereby also wanting to influence, the home-learning environment. Schmidt and Alasuutari (2023) call for more studies on how this transformation and the new ideals benefit some parents more than others – for example by addressing the cultural background of different parents – in relation to the new policies.

The aim is to increase knowledge about factors related to positive interactions between ECEC institutions and multilingual parents, accentuating interactions and collaboration, as well as having pedagogical practice and its actors as the main recipients of the result of the study to be conducted. Our point of departure is a strong rationale for collaboration between ECEC institutions and parents as being advantageous to a child’s development, learning, and well-being, both in the present and in the future (Anders et al., 2019; Bronfenbrenner, 1986; Epstein, 2018; Hamilton et al., 2000; Tallberg-Broman, 2009).

Apart from the perspective of the child, aspects of democracy are emphasised, including the parents’ entitlement to be involved in their children’s upbringing and education (Kunnskapsdepartementet, 2017; Tallberg-Broman, 2009; Tveitereid, 2018). Early childhood teachers’ collaboration with parents depends on the existing form of collaboration in ECEC settings. The same is true for parents’ collaboration with teachers. Approaches and attitudes often predict the collaboration (see Epstein & Sanders, 2006; Henderson & Mapp, 2002; Sheridan et al., 2010).

As stated by Aghallaj and colleagues (2020), high-quality collaboration between ECEC institutions and parents is even more important for multilingual families, even though it presents challenges. Bouakaz and Persson (2007) show that parents with a foreign background are perceived by the preschool staff as being problematic, and in need of awareness about how they should act as parents, in relation to Nordic educational institutions. Challenges identified in Bouakaz and Persson’s study include: perspectives of power and legitimacy in ECEC institutions; the institutional habitus; teachers’ attitudes towards parents with a foreign background; and the parents’ own assumption that they lack social and cultural capital. The study concludes that parents have a wish for greater involvement and collaboration, but this wish is challenged by the obstacles identified. At the same time, studies in heterogeneous and socio-economically exposed areas demonstrate a wish, from the teachers’ perspective, for greater parental involvement. As an example, teachers at ECEC institutions request more parental engagement in their children’s education (Bæck, 2010). In conclusion, earlier research reveals a wish for improved collaboration, expressed by both teachers and parents.

Theory

We interpret ECEC teachers’ collaboration with parents in the context of sociocultural perspectives on interaction and learning (Bakhtin, 2010; Bateson, 2000; Vygotsky, 1978). With a grounding in social psychological perspectives, Urie Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological systems theory has had a great influence on the sociocultural paradigm, in which interaction between individuals is of decisive importance. Bronfenbrenner wanted to move away from a one-sided focus on the individual detached from context (1979, p. 12). His ecological theory describes instead how children develop in a system of relationships affected by four environmental systems: the macrosystem (ideologies and society at large); the exosystem (local communities and organisations); the mesosystem (relationships between different microsystems, such as the relationship between a parent and the child’s teacher); and the microsystem (the individual and relationships between individuals).

Our focus is on the mesosystem’s multisetting participation (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, p. 209). Bronfenbrenner (1979) argues that the connection between settings can be just as important as the individual event in an isolated setting. Children’s well-being and learning are, to a greater extent, conditioned by how the ECEC institutions and parents collaborate, rather than how actual learning takes place (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, p. 3). This is underpinned by the EPPE study in the UK, which showed that mutual commitment and involvement is just as important as instruction in children’s development and learning processes (Siraj-Blatchford & Sylva, 2004).

Previous research

Research on collaboration covers many fields including: socio-economic exposure (Bouakaz & Persson, 2007; Jensen et al., 2015); teachers’ collaboration competence (Ljungren, 2016; Persson, 2015); cultural aspects (Lunneblad, 2013); and children’s development and learning (Anders et al., 2011; Shor, 2005). Initially, three systematic reviews were found in searches, combining the chosen search strings4 with the words ‘systematic* OR review’ (Khalfaoui et al., 2020; Norheim & Moser, 2020; Tveitereid, 2018). These reviews emphasised research conducted between 2000 and 2018. Of these three, one (Khalfaoui et al., 2020) was excluded, as the study focused on the classroom climate in general and not on collaboration.

In addition, another systematic review (Aghallaj et al., 2020) was found using a reference list search (Booth et al., 2022). This review includes research conducted between 2000 and 2018. Throughout the three systematic reviews, the focus is on collaboration between ECEC institutions and multilingual parents, and all the reviews are based on research and theories that frame collaboration as meaningful and beneficial to children’s learning and development (Aghallaj et al., 2020; Norheim & Moser, 2020; Tveitereid, 2018).

The results, similar to the studies referred to above, identify specific challenges related to collaboration between ECEC institutions and multilingual parents. Challenges arise when teachers and parents do not share a common language (Norheim & Moser, 2020), or when attitudes towards the use of language differ (Aghallaj et al., 2020). It is notable that some studies included in the reviews show how parents encourage their children’s use of a minority language, while the ECEC institutions only acknowledge the majority language. On the other hand, some studies also show that parents emphasise the use of the majority language, while ECEC institutions want to acknowledge the children’s multilingual resources (Aghallaj et al., 2020).

Apart from language diversity, asymmetrical power relations are addressed as an element that can affect collaboration in a negative way (Norheim & Moser, 2020). ECEC institutions and teachers are regarded, by both themselves and parents, as experts and those who know what is in the best interests of the child. These assumptions can lead to limited involvement – for example, in parent–teacher conferences (Norheim & Moser, 2020).

Furthermore, the reviews show that diverse cultural, ethnic, and religious backgrounds can generate conflict or a fear of conflict, which can have a deterrent effect (Aghallaj et al., 2020; Norheim & Moser, 2020; Tveitereid, 2018). Norheim and Moser (2020) describe how cultural differences can cause disagreements about discipline or pedagogy, and how parents with a foreign background become more likely to avoid expressing their opinions compared to native parents. Additionally, Tveitereid (2020) states that traditions and religious aspects are seen by the ECEC institutions as a minefield to be avoided. Teachers are afraid to offend parents when addressing unfamiliar topics.

Despite such challenges, these reviews also present factors that are beneficial to collaboration between ECEC institutions and multilingual parents (Aghallaj et al., 2020; Norheim & Moser, 2020; Tveitereid, 2018). Teachers’ ability to have an open attitude, be interested, and have an understanding of diversity (Tveitereid, 2018) is one factor. Another factor is a positive approach toward multilingualism (Aghallaj et al., 2020). Multilingual teachers, signs and other written material in different languages, translanguaging, deliberate efforts to create safe environments, and well-established contacts between parents and ECEC institutions are stressed as positive factors (Norheim & Moser, 2020). The most significant factor facilitating collaboration, which appears in the reviews, is a positive, respectful, and inclusive approach from teachers towards parents (Aghallaj et al., 2020; Norheim & Moser, 2020; Tveitereid, 2018).

Although the reviews all include both barriers to and enablers of collaboration, some limitations could be identified. None of the reviews include studies from later than 2018, and in a fast-growing research society, where the number of publications is continually increasing (Aghallaj et al., 2020), this is a limitation. Two of the reviews include studies only in English, and most of the included results come from countries where English is the majority language (Aghallaj et al., 2020; Norheim & Moser, 2018). The third review, on the other hand, is limited because it includes only Scandinavian studies (Tveitereid, 2018). Although the reviews have some limitations, they all underline the need for more research in the field. Research from the perspective of teachers is called for by Norheim and Moser (2020), while Aghallaj and colleagues (2020) argue for more studies from the parents’ perspective. Tveitereid (2018) highlights the importance of including more than the pedagogical perspective, as the phenomena investigated are multiple and spread across many different research fields. In all systematic reviews presented here, researchers stress the need for studies aiming to find positive factors facilitating collaboration between ECEC institutions and multilingual parents (Aghallaj et al., 2020; Norheim & Moser, 2020; Tveitereid, 2018).

Aim and research questions

As presented above, theory (see Bronfenbrenner, 1979) and earlier research (see Norheim & Moser, 2018) have established that collaboration between ECEC institutions and parents is a vital factor in children’s learning, development, and well-being, especially for children with a foreign background. However, previous research shows challenges relating to linguistic, social, and cultural issues relating to collaboration between ECEC institutions and multilingual parents. In light of an increasing number of people in Scandinavia with a foreign background (SCB, n.d.; SSB, n.d.a, there is a need for research related to the larger number of children growing up in settings where they are exposed to more than one language on a daily basis (Aghallaj et al., 2020). The identified need for research recognising positive factors facilitating collaboration between ECEC institutions and multilingual parents (Aghallaj et al., 2020; Norheim & Moser, 2020; Tveitereid, 2018) will be addressed in this planned systematic review. The planned review is based on the growing multilingual and multicultural society, where collaboration between ECEC institutions and parents is seen as positive for children’s development and learning. Because of the challenges described above, highlighting positive factors will scientifically emphasise those factors that can increase collaboration between two different microsystems in Bronfenbrenner’s mesosystem. Both microsystems affect a child’s possibility to develop, thrive, and learn. The aim of the planned systematic review then is to increase knowledge of, and identify, positive factors related to collaboration between ECEC institutions and multilingual parents. Data will be extracted from studies with multiple research designs and from different research fields. The systematic review will thus contribute a scientifically based overview. The following question will be addressed:

– What factors are identified as positive for facilitating collaboration between ECEC institutions and multilingual parents, and who will benefit?

New and synthesised knowledge is important for both researchers and practitioners, as well as for policymakers, such as governments and universities. However, the primary target of the result of the planned systematic review is pedagogical practice and its actors. By synthesising research from different fields as planned, the identification of positive factors enabling collaboration may have an impact on practitioners, and create new ways of acting in their pedagogical practice, which will be beneficial to children, as well as to parents and practitioners.

Context

Describing complex backgrounds without oversimplification or creating stereotypes can be problematic. The discourse on immigrants is complex, and there is a tendency towards negative generalisation, describing immigrants as problematic and more at risk. The heterogeneity within the ‘group’ of immigrants is often neglected (Gruber, 2007). At the same time, both research (Jakobsen et al., 2019) and statistics (SSB, n.d.b) clearly state that members of multilingual families generally have lower incomes, deal with higher unemployment, get lower grades at school, and more often live in socio-economically disadvantaged areas than members of native families. Studies of ECEC institutions also indicate that collaboration in these areas is reduced (Bouakaz & Persson, 2007), and that the pedagogical learning environment is inferior (Langeloo et al., 2019) and less rigorous for the individual child (Palludan, 2007).

Tveitereid (2020) addresses the danger of simplifying or substantiating stereotypes, as she describes how newly arrived families in Scandinavia are a heterogenic group, and the lingual, cultural, religious, and ethnic backgrounds often differ more within the group than they do between the group and majority families. In the systematic reviews referred to earlier in this protocol, the concept used as criteria for ‘multilingual parents’ varies. Aghallaj and colleagues (2020) use ‘lingual minorities’ for those families where a different language than the majority language is spoken at home. Tveitereid (2018) uses different concepts, such as ‘families with a minority background’, ‘newly arrived families,’ and ‘children and families with different lingual and cultural backgrounds.’ No definition of these concepts is made by Tveitereid (2018). Another way to describe the conditions of the families included in the review is provided by Norheim and Moser (2020), who use the term ‘parents with an immigration background.’

To avoid discussion of the complex and theoretical concepts of culture and identity, the planned systematic review will use the terms multilingual, minority language, and foreign background.5

Early childhood education and care institutions are defined as pedagogical practices for children younger than six years of age. In the search terms, a multitude of definitions are included to capture the international variety of concepts for this practice, such as preschool, kindergarten, and early childhood education (see Table 1).

Method

The planned review will be conducted in the form of a systematic review, as defined by Booth and colleagues (2022), Denscombe (2021), and Granth and Booth (2009). A systematic review searches for, appraises, and synthesises research evidence from all relevant studies on a specific topic, in a methodically and transparent manner (Granth & Booth, 2009). As the aim is to investigate the positive factors facilitating collaboration and to synthesise the results, we chose to conduct the review as a systematic review. This also makes it possible to assess the studies included in the review.

A review protocol following the PRISMA-P guidelines will be registered in the PROSPERO database.

Searches

According to Tveitereid (2018), more perspectives than the pedagogical need to be included in research on collaboration between multilingual parents and ECEC institutions. This need is addressed, and the search will include databases within the fields of educational science, linguistics, sociology, and psychology.

The following databases will be used:

– Academic Search Premier – English

– ERIC EBSCO – English

– IDUNN – Norwegian

– MLA international bibliography with full text – English

– NB-ECEC.org/no

– Oria – Norwegian

– PsycINFO – English

– SCOPUS – English

– SocINDEX – English

– SUMMON – Danish

– SUMMON – Swedish

– Web of Science – English

The following search strings (Table 1) will be combined with AND:

| English | Swedish | Danish | Norwegian Bokmål | Norwegian Nynorsk | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaboration | (“preschool home cooperation” OR “parent teacher cooperation” OR “preschool home collaboration” OR “parent teacher relationship” OR “family school relationship” OR “parent teacher communication” OR “parent* participation” OR partnership) | (föräldrasamverkan OR föräldrasamarbete OR föräldrakommunikation OR ”kommunikation mellan förskola och vårdnadshavare” OR ”kommunikation mellan förskola och föräld*” OR ”förskola och hem” OR ”hem och förskola” OR föräldradeltagande OR samarbete OR samverkan) | (forældresamarbejde OR børnehave og hjem” OR “hjem og børnehave” OR forældredeltagelse OR samarbejde OR deltagelse) | (foreldresamarbeid OR “barnehage og hjem” OR “hjem og barnehage” OR foreldredeltakelse OR samarbeid* OR medvirkning OR “kommunikasjon mellom barnehage og omsorgsperson*” OR “kommunikasjon med foreld*”) | (foreldresamarbeid OR “barnehage og heim OR “heim og barnehage” OR foreldredeltaking OR samarbeid OR medverking OR “kommunikasjon mellom barnehage og omsorgsperson*” OR “kommunikasjon med foreld*) |

| Multilingual | (multilingual* OR bilingual* OR trilingual* OR multicult* OR “foreign background” OR diverse OR immigrant* OR migrant*) | (flerspråk* OR tvåspråk* OR mångkult* OR multikult* OR mångfald OR “utländsk bakgrund” OR invandrar*) | (flersproglig* OR tosproglig* OR multikulturel* OR “udenlandsk baggrund” OR indvandrer* OR immigra*) | (flerspråk* OR tospråk* OR flerkult* OR multikult* OR mangfold* OR “utenlandsk bakgrunn“ OR innvandre*OR tilflytt* OR immigra*) | (fleirspråk* OR tospråk* OR fleirkult* OR multikult* OR mangfald* OR “utanlandsk bakgrunn“ OR innvandre* OR tilflytt* OR immigra*) |

| ECEC | (pre-school OR preschool OR kindergarten OR “early childhood education” OR ECE OR ECEC) | (förskola) | (børnehave* OR førskole* OR vuggestue) | (barnehage OR førskole) | (barnehage OR førskule) |

Full search strategies (Booth et al., 2022) will be used, and reference sections will also be handsearched for any overlooked literature (Krumsvik, 2016).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The referenced reviews include studies published until 2018 (Aghallaj et al., 2020; Norheim & Moser, 2020; Tveitereid, 2018). Today the pace of publication is increasing, and the research field is expanding (Johnson et al., 2018; Norheim & Moser, 2020), which provides motivation for a new review including studies completed between 2015 and 2023. A review of recent studies is also relevant, as large parts of the world have experienced significant refugee movements during recent decades, as was particularly the case when the Scandinavian countries and Europe received a large number of refugees and immigrants during what has been called ‘the refugee crisis of 2015’ (Nationalencyklopedin, n.d.). This affects the demographics, culture, and linguistics of the Scandinavian countries, and the ECEC institutions are important meeting points between cultures and languages (Bouakaz, 2007; Ljunggren, 2016). Research conducted beyond 2015 is therefore relevant to include (see Table 2).

The objective in the planned review, that is ‘positive factors facilitating cooperation between ECEC institutions and multilingual parents,’ may be found in non-scientific reports or writing from development projects carried out in ECEC institutions – what is described as ‘grey literature’ (Booth et al., 2022). Grey literature will not be included in the planned review, as the aim is to contribute a review of scientifically based knowledge about positive factors enabling collaboration between ECEC institutions and multilingual parents. Nordic (Danish, Finnish, Icelandic, Norwegian and Swedish) PhD theses are included in the searches as these are both peer-reviewed and published (University of Helsinki, n.d.; University of Skövde, 2022).

The studies included have multilingual or bilingual parents as part of the study’s research object. Studies presenting both negative and positive factors for collaboration will be included, but only the positive factors will be included in the following synthesis. Studies that focus exclusively on challenges or negative aspects will be excluded.

| Included | Excluded | |

|---|---|---|

| Timeframe | 2015–2023 | |

| Population | Studies with multilingual caregivers or caregivers speaking another language than the majority language in ECEC institutions.

Studies following different perspectives: the teacher’s, the caregiver’s and/or the children’s. |

Studies of parents who are unilingual and speak the same language as the majority language. |

| Teaching level | ECEC institutions, kindergarten, preschool for children between one and six years of age. | Institutions and schools for children over the age of six. |

| Publication type | Studies published in English, Norwegian (Bokmål and Nynorsk), Danish or Swedish.

Studies that draw on quantitative data. Studies that draw on qualitative data. Studies that draw on both quantitative and qualitative data. Peer-reviewed articles. Nordic PhD theses. Empirical studies. |

Systematic reviews, included in the background in the article but not in the review.

Grey literature such as government reports, non-scientific project descriptions, student literature. |

| Phenomena of interest | Studies that address the collaboration between ECEC institutions and parents6.

Studies that show positive factors for collaboration. Positive factors in this case are factors described or expressed as positive, good, effective, encouraging, optimistic, constructive, successful, efficient, useful, inspiring, productive, motivating, stimulating, beneficial, valuable, important, meaningful, or helpful for collaboration between preschools and parents.7 |

Studies that do not include collaboration between ECEC institutions and parents.

Studies focusing on families or children in need of special educational provision and support. Studies that do not include positive factors for collaboration. |

Appraisal

All records identified in the search strategy will be exported to EndNote software. Duplicate articles will be removed. The search and extraction methods will be presented in the PRISMA flow chart, showing the included and excluded studies, with the reasons for exclusion and the dates of searches (Page et al., 2021).

As the studies included in the search are quantitative, qualitative, and mixed method studies, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) developed by Hong and colleagues (2018a) will be used for assessing the quality of the included studies. The MMAT is a tool that will appraise the research quality of different types of studies, such as qualitative research, quantitative descriptive studies, and mixed methods studies in the same review (Hong et al., 2018b). In the proposed review, the MMAT appraisal will be conducted for all extracted studies, and only those studies that meet all the criteria in the MMAT will be included in the thematic synthesis (Thomas & Harden, 2008).

The data will be extracted into Microsoft Excel using a created extraction form based on PerSPEcTiF (Booth et al., 2022). In addition, factors defined as positive, good, effective, encouraging, optimistic, constructive, successful, efficient, useful, inspiring, productive, motivating, stimulating, beneficial, valuable, or helpful will be extracted. Finally, the concepts for defining multilingual families, any possible benefits to the children, and the perspective the study takes will be extracted.

Data synthesis

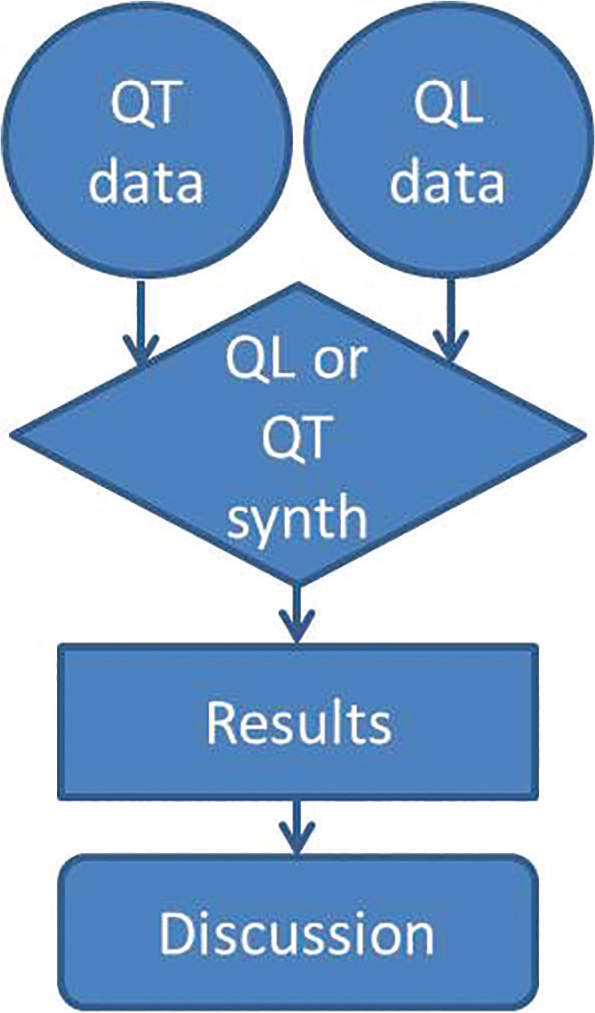

The synthesis of data will be convergent, in that it integrates different data and methods of analysis from qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method studies together. (Munthe et al., 2022). Convergent systematic reviews could, according to Gough (2015), be ‘described as having broad inclusion criteria for methods of primary studies and have special methods for the synthesis of the resultant variation in data’ (p. 2). The included studies will be synthesised in the following way (Figure 1), as described by Hong and colleagues (2017).

Figure 1. Convergent data synthesis (Hong et al., 2017, p. 9)

Syntheses will be conducted by the development of ‘themes of positive factors.’ This will draw on the thematic synthesis described by Thomas and Harden (2008), and aims to code the data, develop descriptive themes, and finally generate analytical themes. This method of synthesising the data will be applied to the factors described as positive, good, effective, encouraging, optimistic, constructive, successful, efficient, useful, inspiring, productive, motivating, stimulating, beneficial, valuable, or helpful for collaboration between ECEC institutions and multilingual parents, and for whom these factors are defined as positive. According to Thomas and Harden (2008), ‘the development of descriptive themes remains “close” to the primary studies, the analytical themes represent a stage of interpretation whereby the reviewers “go beyond” the primary studies and generate new interpretive constructs, explanations, and hypotheses’ (p. 1). In accordance with the aim and research question, this way of synthesising the data is a possible and suitable method for including all positive factors enabling collaboration found in the included studies. This way of synthesising will also be utilised for both quantitative and qualitative data, and the themes developed can include data of different types.

Risk of bias

The risk of bias assessment helps to establish the transparency of results and findings. When conducting a systematic review, the risk of bias should be limited as much as possible (Booth et al., 2022). This includes the search, the extraction, the assessment, the synthesis, and the interpretation. For the planned systematic review, the search strings have been discussed within the author group, as well as with librarians. The extraction will be performed by the three of us, as authors of this protocol. Two of us will then independently screen the titles and abstracts of the identified articles. The full texts of eligible studies will be read thoroughly by two of us, as reviewers, to assess their suitability. The third reviewer will then be consulted in the event of a conflict between the two reviewers after a consensus discussion is held. The same procedure will take place for the assessment and thematical synthesis to limit bias in the result (see Table 3).

Additionally, the risk of bias in systematic reviews tool (ROBIS) (University of Bristol, n.d.) will be applied by the research team to assess the risk of bias in all parts of the review. This team includes researchers with diverse experience from research and assessment of studies that draw on both quantitative and qualitative data, which, as stated by Booth and colleagues (2022), is necessary for a valid result in the review. If necessary, other researchers will be consulted to overcome any expertise gaps.

| Stage | Month | Author involvement | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

| Search | 1 | |||||||

| Screening and extracting | 1, 2, 3 | |||||||

| Assessing | 1, 2, 3 | |||||||

| Synthesising | 1, 2, 3 | |||||||

Planned outcome

The result will be presented in two ways: as a compressed list of positive factors, categorised in themes resulting from thematic synthesis; and as written text, where the analytical themes will be described and developed. Finally, the result will be discussed and placed in the context of earlier research. The pedagogical research field and practices are the main recipients of this increased knowledge of positive factors related to collaboration between ECEC institutions and multilingual parents.

Funding details

This work was supported by the Research Council of Norway under Grant number 319918.

References

- Aghallaj, R., Van Der Wildt, A., Vandenbroeck, M., & Agirdag, O. (2020). Exploring the partnership between language minority parents and professionals in early childhood education and care: A systematic review. In C. Kirsch & J. Duarte (Eds.), Multilingual approaches for teaching and learning: From acknowledging to capitalising on multilingualism in European mainstream education. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429059674

- Anders, Y., Cohen, F., Ereky-Stevens, K., Trauernicht, T., Schünke, J., & Köpke. S. (2019). Inclusive education and social support to tackle inequalities in society. In ISOTIS report D3.5. Integrative Report on parent and family-focused support to increase educational equality. Funded by European Union’s Horizon 2020 (Grant Agreement No. 727069). https://staging-isotis-pw.framework.pt/site/assets/files/1605/d3_5_integrative_report.pdf

- Bakhtin, M. M. (2010). Speech genres & other late essays. University of Texas Press.

- Bateson, G. (2000). Steps to an ecology of mind. University of Chicago Press.

- Booth, A., Sutton, A., Clowes, M., & Martyn St-James, M. (2022). Systematic approaches to a successful literature review (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Booth, A., & Grant, M. J. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Bouakaz, L. (2007). Parental involvement in school: What hinders and what promotes parental involvement in an urban school [Doctoral dissertation]. Malmö University.

- Bouakaz, L., & Persson, S. (2007). What hinders and what motivates parents’ engagement in school? International Journal About Parents in Education, 1, 97–107.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22(6), 723–742. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.22.6.723

- Bæck, K. U. (2010). ‘We are the professionals’: A study of teachers’ views on parental involvement in school. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 31(3), 323–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425691003700565

- Council of Europe. (2023, August 10). Languages of schooling. Languages of schooling – Language policy.

- Denscombe, M. (2021). The good research guide: Research methods for small-scale social research projects (7th ed.). Open University Press.

- Epstein, J. (2018). School, family, and community partnerships, student economy edition: Preparing educators and improving schools. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429493133

- Epstein, J. L., & Sanders, M. G. (2006). Prospects for change: Preparing educators for school, family, and community partnerships. Peabody Journal of Education, 81(2), 81–120. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327930pje8102_5

- Gough, D. (2015). Qualitative and mixed methods in systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 181–181. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-015-0151-y

- Gruber, S. (2007). Skolan gör skillnad: Etnicitet och institutionell praktik [Doctoral dissertation]. Linköping University.

- Hamilton, R., Anderson, A., Frater-Mathieson, K., Loewn, S., & Moore, D. (2007). Literature review: Interventions for refugee children in New Zealand Schools: Models, methods, and best practices. Ministry of Education.

- Henderson, A. T., & Mapp, K. L. (2002). A new wave of evidence: The impact of school, family, and community connections on student achievement. Annual synthesis, 2002. National Center for Family & Community Connections with Schools. Southwest Educational Development Laboratory.

- Hong, Q. N., Pluye, P., & Bujold, M. (2017). Convergent and sequential synthesis designs: Implications for conducting and reporting systematic reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Systematic Reviews, 6, 61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0454-2

- Hong, Q. N., Pluye, P., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F. K., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M., Griffiths, F. E., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M. C., & Vedel, I. (2018a). The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34, 285–291.

- Hong, Q. N., Pluey, P., Fábregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.-P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., & Rousseau, M.-C. (2018b, August 1) Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018: User guide. McGill. http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf

- ISOF. (2021, August 26). Vad är ett minoritetsspråk? [What is a minority language?] https://www.isof.se/stod-och-sprakrad/vanliga-fragor-och-svar/fragor-och-svar/vad-ar-ett-minoritetssprak

- Jakobsen, V., Korpi, T., & Lorentzen, T. (2019). Immigration and integration policy and labour market attainment among immigrants to Scandinavia. European Journal of Population, 35, 305–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-018-9483-3

- Jensen, N. R., Petersen, K. E., & Wind, A. K. (2015). Daginstitutionens betydning for udsatte børn og deres familier i ghetto-lignende boligområder [The impact of ECEC institutions in the lives of at-risk children and their families in ghetto-like living areas]. AU Library Scholarly Publishing Services. https://doi.org/10.7146/aul.18.16

- Johnson, R., Watkinson, A., & Mabe, M. (2018). The STM report: An overview of scientific and scholarly publishing (5th ed.). STM. Retrieved 23-02-26 from https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1575771/2018_10_04_stm_report_2018/2265545/

- Khalfaoui, A., García-Carrión, R., & Villardón-Gallego, L. A. (2021). Systematic review of the literature on aspects affecting positive classroom climate in multicultural early childhood education. Early Childhood Education Journal 49, 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-020-01054-4

- Krumsvik, R. J. (Ed.). (2016). En doktorgradsutdanning i endring [A changing doctoral dissertation programme]. Fagbokforlaget.

- Kunnskapsdepartementet. (2017). Rammeplan for barnehagen: Forskrift om rammeplan for barnehagens innhold og oppgaver [Framework plan for kindergartens]. https://www.udir.no/laring-og-trivsel/rammeplan-for-barnehagen/

- Lane-Mercier, G., Merkle, D., & Koustas, J. (Eds.). (2018). Minority languages, national languages, and official language policies. Queen’s University Press.

- Langeloo, A., Mascareño Lara, M., Deunk, M. I., Klitzing, N. F., & Strijbos, J. W. (2019). A systematic review of teacher–child interactions with multilingual young children. Review of Educational Research, 89(4), 536–568. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654319855619

- Ljunggren, A. (2016). Multilingual affordances in a Swedish preschool: An action research project. Early Childhood Education Journal, 44(6), 605–612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-015-0749-7

- Lunneblad, J. (2013). Tid till att bli svensk: En studie av mottagandet av nyanlända barn och familjer i den svenska förskolan [Time to become Swedish: A study of how newly arrived children and families are received in the Swedish preschool]. Nordisk Barnehageforskning, 6. https://doi.org/10.7577/nbf.339

- Markström, A., & Simonsson, M. (2017). Introduction to preschool: Strategies for managing the gap between home and preschool. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 3(2), 179–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2017.1337464

- Munthe, E., Bergene, A. C., ten Braak, D., Furenes, M. I., Mathisen Gilje, T., Keles, S., Ruud, E., & Wollscheid, S. (2022). Systematisk kunnskapsoppsummering utdanningssektoren [A systematic knowledge summary of the educational sector]. Norsk Pedagogisk Tidskrift, 106(2), 131–144. https://doi.org/10.18261/npt.106.2.5

- Nationalencyklopedin. (n.d.). Flyktingkrisen 2015 [The immigrant crisis 2015]. Retrieved August 10, 2023 from: http://www.ne.se/uppslagsverk/encyklopedi/lång/flyktingkrisen-2015

- Norheim, H., & Moser, T. (2020). Barriers and facilitators for partnerships between parents with immigrant backgrounds and professionals in ECEC: A review based on empirical research. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 28(6), 789–805. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2020.1836582

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L. A., & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372(71). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Palludan, C. (2007). Two tones: The core of inequality in kindergarten? International Journal of Early Childhood, 39(1), 75–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03165949

- Persson, S. (2015). En likvärdig förskola för alla barn: Innebörder och indikatorer [An equal preschool for all children]. Vetenskapsrådet.

- SCB. (2002). MIS, personer med utländsk bakgrund, riktlinjer för redovisning i statistiken [Statistics on persons with foreign background: Guidelines and recommendations]. SCB. https://www.scb.se/contentassets/60768c27d88c434a8036d1fdb595bf65/mis-2002-3.pdf

- SCB. (n.d.). Antal personer med utländsk eller svensk bakgrund (fin indelning) efter region, ålder och kön. År 2002–2021 [Persons with foreign background: Statistics]. Retrieved 14 March, 2023 from https://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/sv/ssd/START__BE__BE0101__BE0101Q/UtlSvBakgFin/

- Schmidt, L. S. K., & Alasuutari, M. (2023). The changing policy ideals for parental cooperation in early childhood education and care. Global Studies of Childhood. https://doi.org/10.1177/20436106231175028

- Sheridan, S. M., Knoche, L. L., Edwards, C. P., Bovaird, J. A., & Kupzyk, K. A. (2010). Parent engagement and school readiness: Effects of the getting ready intervention on preschool children’s social-emotional competencies. Early Education and Development, 21(1), 125–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409280902783517

- Shor, R. (2005). Professionals’ approach towards discipline in educational systems as perceived by immigrant parents: The case of immigrants from the former Soviet Union in Israel. Early Child Development and Care, 175(5), 457–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/0300443042000266268

- Siraj-Blatchford, I., & Sylva, K. (2004). Researching pedagogy in English pre-schools. British Educational Research Journal, 30(5). https://doi.org/10.1080/0141192042000234665

- Skolverket. (2018). Läroplan (Lpfö18) för förskolan [Curriculum for preschool]. Skolverket https://www.skolverket.se/undervisning/forskolan/laroplan-for-forskolan/laroplan-lpfo-18-for-forskolan

- SSB. (n.d.a). Innvandrere [Immigration]. Retrieved 14 March 2023 from https://www.ssb.no/innvandring-og-innvandrere/faktaside/innvandring

- SSB. (n.d.b). Innvandrere og norskfødte med innvandrerforeldre [Immigrants and Norwegian-born with immigrant parents]. Retrieved 14 March 2023 from https://www.ssb.no/befolkning/innvandrere/statistikk/innvandrere-og-norskfodte-med-innvandrerforeldre

- Tallberg-Broman, I. (2009). “No parent left behind”: Föräldradeltagande för inkludering och effektivitet [Parental participation for inclusion and efficiency]. Educare, (2–3).

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology 8, 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

- Tveitereid, K. (2018). Inkludering i barnehagens felleskap: Samarbeid mellon minoritetsfamilien och barnehagens personale. En systematisk litteraturgjennomgang 2012–2017 [Inclusion in the kindergarten community]. PADEIA (16).

- University of Bristol. (n.d.). ROBIS: Tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews. Retrieved 14 March 2023 from https://www.bristol.ac.uk/media-library/sites/social-community-medicine/robis/ROBIS%201.2%20Clean.pdf

- University of Helsinki. (n. d.). Anvisningar om granskning av doktorsavhandlingar [Instructions for the examiners of doctoral dissertations]. Retrieved August 8, 2023 from https://www.helsinki.fi/sv/humanistiska-fakulteten/forskning/doktorsutbildning/anvisningar-om-granskning-av-doktorsavhandlingar

- University of Skövde. (2022, October 8). Bedömning av dokorsavhandling och disputation [Assessment of a PhD thesis and defense]. https://www.his.se/forskning/doktorandhandbok/disputation/bedomning-av-doktorsavhandling-och-disputation/

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

- Wedin, Å. (2017). Språkande i förskolan och grundskolans tidigare år [Language in preschool and early years education]. Studentlitteratur.

Fotnoter

- 1 The search strings defined in Table 1 are more extensive and allow the search to capture relevant literature applying terms other than those described here.

- 2 For an expanded discussion of the concept of majority and national language, see e.g., Lane-Mercier et al. (2018).

- 3 These concepts are not unproblematic, and a discussion about definitions is included further on.

- 4 See Table 1.

- 5 As defined in the introduction.

- 6 Other words might be used to describe collaboration between ECEC institutions and parents, such as partnership or cooperation, but it is the phenomenon of collaboration that needs to be addressed for the study to be included.

- 7 This can be adjusted if needed during the search process.